The term gerrymandering was coined over 200 years ago. On March 26, 1812, the Boston Gazette first used the term in describing the redrawing of a Massachusetts state senate district. Gov. Elbridge Gerry, a member of the Democratic-Republican Party, said the district resembled a salamander. Gerry’s name was linked to the last part of salamander, and the term gerrymandering was born.

Gerry and his party lost the House and governorship to the Federalists, but the Democratic-Republicans won the gerrymandered state senate district. Gerrymanders have been part of the political process ever since then.

The federal courts have refused to interfere with the drawing of political districts lines, arguing this was a “political question” best left to the legislature and not the courts.

The only exception made by the courts relates to “racial gerrymandering,” which the courts have found to violate the “equal protection” clause of the constitution. Partisan gerrymanders have essentially remained outside of the court’s jurisdiction.

Increasingly, it is getting difficult to tell what may be a racial as opposed to partisan gerrymander. When better than 90 percent of black voters vote Democrat, how do you determine if the gerrymander was done for racial or partisan reasons? Also, at one point, the courts were requiring the states to create as many majority-minority districts as possible in order to increase minority representation. Now, the courts are urging states to reduce the percentage of minority voters in a district. Few areas have had as much inconsistency from the courts as reapportionment and gerrymandering.

Although the U.S. Supreme Court has not intervened in partisan gerrymanders, the court came close in 2004 when they split 4-4 in a Pennsylvania partisan gerrymandering case. Justice Anthony Kennedy, who voted to uphold the gerrymander, said he “would not foreclose” the possibility of relief “if some limited and precise rationale were found to correct an established violation of the Constitution in some redistricting cases.”

A partisan gerrymandering case in Wisconsin is now under review by the U.S. Supreme Court. At issue is the “efficiency gap,” a tool developed by a law professor and political scientist which purports to measure excessive partisan gerrymanders.

In 2010, after 40 years of Democratic dominance, Republicans gained control of the legislature and governor’s office. They redrew the legislative district lines so that 49 percent of the voters elected Republicans to 60 of the 99 Assembly seats.

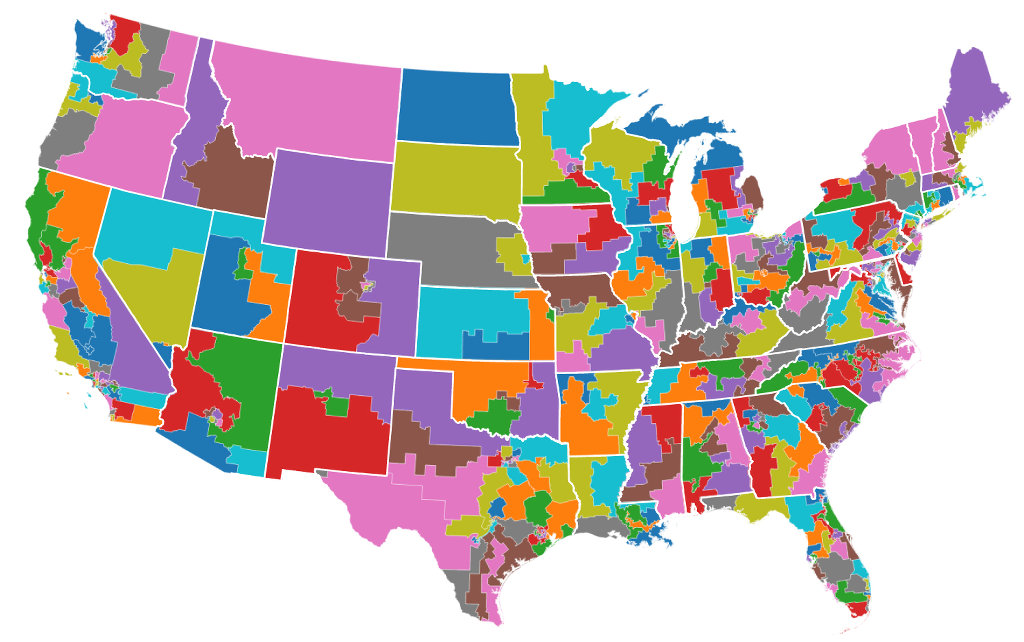

On the national level, even though Republicans won less than half the House votes, they won 241 of the 435 House seats. The Brennan Center for Justice found that Republicans have a “durable majority” of 16-17 seats in the House, mostly in seven states where Republicans drew the district lines.

Courts have already struck down lines in North Carolina, Virginia, Florida and Texas due to illegal gerrymandering. The Wisconsin gerrymander has been described as “the largest partisan asymmetry on record.”

With digital technology, it is easier to carve out partisan districts with surgical precision. As Sam Wang and Brian Remlinger of the Princeton Gerrymandering Project note, “Thanks to technology and political polarization, the effects of partisan gerrymandering since 2012 have been more pronounced than at any point in the previous 50 years.”

Does the Court now have the tools to ascertain a party gerrymander that Justice Kennedy said was needed to outlaw partisan gerrymandering? They better have found a precise tool since, if the court rules against the Wisconsin gerrymander, they will also strike down similar gerrymanders in one-third of the 50 states.

As Chief Justice John Roberts noted in his remarks on the Wisconsin case Oct. 3, the courts “authority and legitimacy” would be hurt if it struck down legislative districts in so many states. “That is going to cause very serious harm to the status and integrity of this court in the eyes of the country.”

Republicans argue that the Wisconsin map reflects the fact that Democrats have packed themselves into cities, while Republicans are better distributed across the state.

Judge Kenneth Ripple, one of the two district court judges who struck down the Wisconsin gerrymander, agrees that “the high concentration of Democratic voters in urban centers like Milwaukee and Madison, affords the Republican Party a natural, but modest advantage in the districting process.”

But, noted Ripple, partisan gerrymandering amplified that advantage.

Will that be enough for the court to throw out legislative boundaries in one-third of the states? We will know when the court hands down its decision in a few months.

___

Darryl Paulson is Emeritus Professor of Government at USF St. Petersburg specializing in Florida politics and elections.